Sharpening hand saws

The battered and dulled Slack

Sellars & Co saw only needed

de-rusting and sharpening to

give it years more useful life

Rust coated both faces of the blade and so I suspected the development of rust inside the handle where the wood has direct contact with both the steel blade and the back stiffener. Removing the handle revealed a mass of deep rust. You can remove the back of the saw but I’m always cautious of this because it may be hard or even impossible to put it back later. My advice is to leave well alone.

Cleaning up the saw, removing the handle and flattening the teeth back to their original shape.

Re-shaping the handle and flattening the teeth before re-sharpening.

Flattening, waxing and clamping the saw in position.

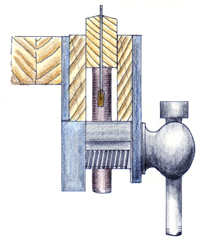

To remove the kink, I planished the surface of the saw directly on and round the kink on the risen side with a hammer and small benchtop anvil. This drives the metal back into the blade and with judicious strikes will generally straighten out the kinks.

For crooked areas along the teeth, simply tap along the back of the stiffening bar. Shocking this pinching spline draws the steel blade into the stiffener. Trial and error will establish where to tap. This isn’t an exact science.

Wherever the router didn’t reach, I used a rasp and file to remove the waste and then sanded with progressively finer grits to 220-grit. To scrape the rounded parts of the handle, try a spare razor saw blade, the one I had used earlier to remove the excess rust. I filed a clean square edge and sharpened it as you would a traditional scraper. The thinness allowed me to flex it to conform it to the shape I wanted. Two or three coats of boiled linseed oil gave me the protection I needed.

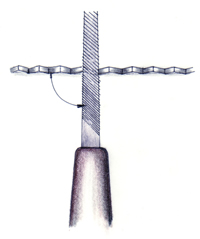

The saw teeth on this saw were irregular in shape, a common fault with old or secondhand saws. It’s a fairly simply process to joint them straight and establish consistent teeth. Saws are sized by the number of teeth that occur within a given measurement. In this case we use points per inch as the standard method. Because these teeth are uneven, every other tooth must be reduced to allow the adjacent teeth to grow.

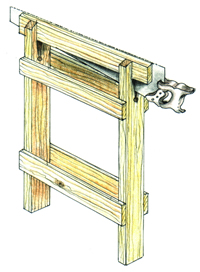

Secure the saw in the vise between two battens and use a flat, single-cut mill file to level the oversize teeth. With a suitably sized saw file, work on the obviously over-sized teeth first by filing either side of the larger teeth to reduce their widths. Use the flat mill file to take off the tops of all the teeth with a couple of strokes. This will leave flat tops to any oversized teeth while missing the lower smaller ones.

Further correct the oversized teeth by filing each side of them until they come to a point. Be aware of the adjacent teeth as you don’t want to recreate the problem on the other teeth. I used a 4in extra, extra slim taper for this particular saw, which has 15-PPI.

Your saw filing should have corrected any major discrepancies. If so, you can now file all of the teeth to even out minor differences. Simply look at each of the teeth as you file them and apply pressure to force the file into the sides of the teeth you need to change.

If no change is needed, apply pressure to press the saw file into the bottom of the gullet and use long, even strokes to file both sides of the teeth. If the saw is in particularly bad shape, take two or three strokes but do the same to every tooth, otherwise you’ll create an uneven line to the teeth.

If the saw is in good shape, file with a single stroke. You will be filing every alternate gullet, which sharpens the front of one tooth and the back of the adjacent tooth. Begin at one end and skip every other tooth.

I’m sharpening this saw as a non-aggressive ripsaw, which means I can use it equally for crosscut and rip-cut. The pinnacle-point teeth we generally use on more refined crosscut saws is more complex to explain and understand, while the actual method is only marginally better when it comes to cutting the wood, and so the method outlined here is ideal for beginning woodworkers to master.

Flattening teeth and resetting and checking the saw for alighment.

Finally, place the saw on fine

sharpening plates and rub the

saw back and forth for a few

rubs. This will both polish and

fine-tune the outside cutting

corners of the teeth

For nail-punch setting I lay the saw on its side with the teeth on a thin batten of wood so that the saw is raised up above the workbench. I also lay a batten under the back stiffening bar, to suspend the saw up on the bench.

This saw had no set at all, and so I didn’t have to follow the direction of the existing set. Otherwise, I would simply drive the teeth according to the existing pattern. If the existing set seems irregular, tap the sides of the teeth with a hammer on a steel surface or an anvil to remove the set.

1. Using a setting tool

2. Keeping a file at right

angles for a ripsaw set.

With the setting completed, try the saw. It may feel coarse, if so, then it’s likely that you have too much set. Take the saw back to the anvil or metal vise jaw and tap the sides of the teeth evenly, first from one side of the saw, and then the other.

Try the saw again and compare the cut. This tapping does not remove all of the set because the steel has memory. Tapping the steal compresses the steel between the hammer and the face of the anvil, but the teeth spring back after the hammer blows, but to a more uniform level.

- Log in or register to post comments