Finding David Oldfield

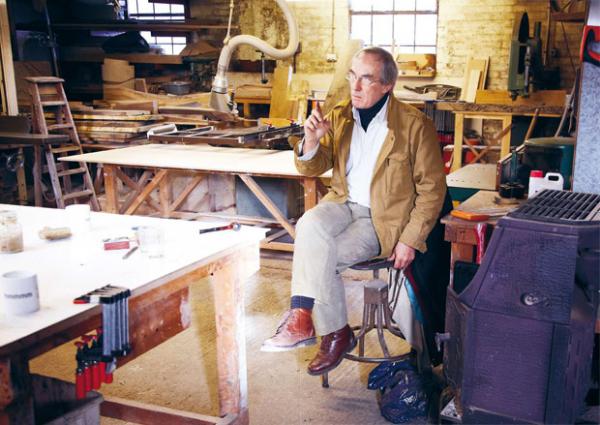

In Wiltshire, not far from Trowbridgeshireton, beside a water meadow in the curtilage of a farm that’s home to a small community of craftspeople, you’ll find David Oldfield. Or rather, you probably won’t: there’s no sign on the door, no giveaway stacks of timber. “No-one knows I’m here,” he says with the dolorous satisfaction of the successful recluse. Even if you do discover his workshop, the personality behind the door isn’t easy to pin down.

He describes himself as a cabinetmaker and designer, and for David the two are inseparable: “I never accept drawings. Well, you’ve got to have some freedom, haven’t you?” And this freedom is a theme to which he returns frequently because, in David’s mind at least, a cabinetmaker-designer is rarely ever free.

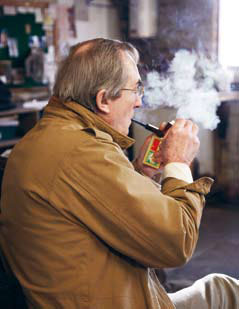

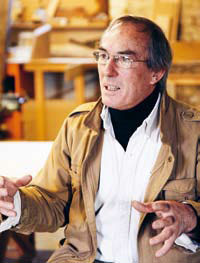

On first acquaintance, you wouldn’t imagine that this is a condition that troubles David. For a start, he has the energy of a free spirit. Oh sure, brought to a standstill by the camera, as he is here, you might guess that he’s a sexagenarian and a grandfather. But see him in pipe-lighting, match-tossing, expansively gesturing action and he has the vitality of someone far younger. As he leaps from idea to reminiscence to argument David speaks in the way that some people sketch, with quick bold strokes that capture the thought before it’s lost; his eyebrows semaphore emphasis, like heavy underlining. So it’s: “Come in.” Allencompassing gesture. “Workshop. Very cold; sorry. Only just lit the stove. Coffee?” Then he’s off on a hunt for mugs to wash, sketching – I mean talking – furiously as he goes. Coffee, milk and water are more or less spooned and poured into the same mug, then David’s reinstalled on his stool by the stove but no less in motion for all that: undertaking a commission, he explains, is an opportunity for adventure, and David knows all about adventurous journeys.

In his own words: “Contributing to the world of three dimensions is a fascinating and worthwhile pursuit. Ambition, enthusiasm, and conviction are all part of the amalgam required when taking up the challenge of a new commission. “An admiration of romantic classicism of line and form is sometimes reflected in my work, but I do not feel bound by it. Stance, whimsey and humour can all be indulged when striving to create a new piece. Creativity is a precarious world of head, heart and hand, which I feel privileged to be part of, and an expensive liberty that I will always afford.”

Though he’d been interested in woodwork since he was a boy, “in schools in the Sixties, anything creative was considered unimportant.” He did manage a year at the Winchester School of Art, “but I was shoved into civil engineering by my Dad, who thought that solid, practical training was what I needed.” When the engineering company went bankrupt and his father died, however, David went into what he calls a ‘state of shock’. He moved to London and tried to live on his wits as a folksinger, sharing a house with one of the Strawberry Hill Boys, the band that went on to become The Strawbs. But increasingly he found that London and a life of no money and no sleep was becoming claustrophobic. It’s easy to imagine, then, how he found himself on a dockside, with a packed trunk and no idea where the ship he was about to board was headed. “All the way round,” the bo’sun told him. “All the way round the ****in’ world.” And that’s how David ended up in New Zealand for 15 years, working mainly as a production manager for a film company – “a hard-drinking lifestyle spent on the run,” as he describes it. In a chance visit to a furnituremaker’s workshop, however, “my lifestyle changed all of an instant” – he was seduced by the seeming peace and quiet. “I decided to resign and learn to make furniture. Frightened myself to death. The day I left the film company, though, I realised that the most successful way to live your life is to do something individually.” It was also the day that he began to realise just how hard it is to achieve that idealised life of cabinetmaking peace and simplicity – even in a workshop rented to you by an old dowager for the princely sum of $15 a week!

The peace and quiet that David discovered on a chance visit to a furnituremaker’s workshop changed his life...

...and frightened him to death! After all, that peace and quiet can be as challenging as a blank piece of paper, waiting to be filled with work and creativity

When David returned to England in 1979 he was what he calls, “a neo-colonial who didn’t play the game as it was played in the more conservative motherland.” For example, he quizzed John Makepiece on the life of the designer-maker, never thinking that the John Makepieces of the world don’t like to be cross-examined about the living they make. “I had a head full of weird ideas,” he recalls, “but I didn’t know where I fitted in.”

When David returned to England in 1979 he was what he calls, “a neo-colonial who didn’t play the game as it was played in the more conservative motherland.” For example, he quizzed John Makepiece on the life of the designer-maker, never thinking that the John Makepieces of the world don’t like to be cross-examined about the living they make. “I had a head full of weird ideas,” he recalls, “but I didn’t know where I fitted in.”

The unvarnished truth is that, back then, he probably didn’t fit into the world of conventional commercial furnituremaking. Those ‘weird ideas’ were the product of his unrequited enthusiasm for Expressionism, and, “Expressionism has nothing to do with convention. It is the world of ‘if’ where a chair, say, can be anything as long as you can sit in it. You’re free to experiment with anything you like; to make shapes any way you want; to be foolish, bizarre, humorous, useless or whatever. Sadly, I’ve done little of it [Moonbase One, shown above, is one of David’s purely Expressionist pieces] but while indulging in this genre, I have felt free of the normal structured existence known to most of us.”

And there’s the rub. The reason that he’s done so little of it is that the freedom of mind and freedom of time to create speculatively is dearly bought, perhaps too dearly. “Expressionism is as near to art as a cabinetmaker can get” – he cites the Fred Baier sideboard that was made just as Picasso painted it, and becomes animated at the thought of Carl Handy’s wilting violins (GW193:50) — “but as far as I know, most Expressionist pieces are made speculatively, which is the financial kiss of death. The pieces are usually only purchased by rich collectors.”

Ann Hartree cautioned him against extremes of artistic idealism when he visited her Prescott Gallery in Banbury shortly after returning to the UK. If he was set on making speculative pieces, she told him, then he was going to need some sort of alternative income if he was to survive.

“The tragedy of being a cabinetmaker,” David reflects, “is that everything you make has to have a use, or a usefulness is expected of the object that you make. Sculptors and 3D artists don’t suffer from this, so why should we?” Well, you can question the way things are all you like, but at the end of the day, says David, “you have to make up your mind about what you want to be.”

David made up his mind – he wanted to be busy, creative, but solvent – and for a dozen called Henry, by the way— will add three days’ of extra work to the three months that the job is already expected to take.

All of which brings us back to a cold workshop and a David Oldfield who has survived three recessions since the day that he imagined making furniture was a way to achieve peace and quiet. “Cabinetmaking is an honest and honourable trade, profession, whatever you want to call it. It’s a good life, but a tough life. Very precarious; you know what debt is all about. And that simplicity,” he reflects, “is one of the hardest things to achieve. I feel sad for the things I haven’t done, and I yearn to make things that I probably never will.”

He hasn’t done and may never do these things because while he’s single-minded about his work – “My work is my life. I have a wife and three children, and sparks have flown over the time I spend in the workshop” – he’s always stopped short of the selfishness that he believes characterises many of the artists who’re remembered by history.

“Still, you have to do what you can,” he says. And what David can do is to take control of the timber and the design, which is in turn a way, he believes, of achieving freedom by controlling and shaping your environment. “If you can work a material that wants to move and fight back then you’ve achieved something in a world where so many of us are buffeted by our work, or by the bank manager, or whatever.”

Does that all sound a little dour? It isn’t meant to. It’s simply supposed to explain that David Oldfield isn’t easy to find because he occupies a creative space between the repetitive work of commercial cabinetmaking; a space whose entrance is just as wide as the latitude afforded by his client’s trust. From the outside, it may look awfully narrow, but step inside, where you can see the freedom he has to indulge his imagination, and you find that there’s room enough to last a lifetime.

- Log in or register to post comments