Glue & joint secrets

How bits of wood are held together with glue has to be one of the most fascinating and magical aspects of this craft, especially for the non-academic among us. Curiously,many of the mechanical joints that have evolved over centuries, before glues became reliable, are still unquestionably used today such as the mortise & tenon, yet tradition is suddenly being challenged in other aspects of woodworking.

A current fad in the world of YouTube woodworking is ‘myth busting’ and mostly from the other side of the pond. YouTube today is undoubtedly the greatest influencer of woodworking practice, replacing what was taught in schools decades ago, but more than that – the many clickbait monetised titles are now suddenly challenging – cancelling – tradition, while at the same time continuing to endorse tradition in many other videos. How to cut dovetails is still a Holy Grail joint. Now, I never envisaged I would be defending tradition when I spent most of my furniture making career challenging it, but it’d be both arrogant and ignorant to negate centuries’ worth of woodworking knowledge. In fact, in 1985, I wrote that ‘Tradition without innovation is stagnant and innovation without tradition is frivolous’.

There are things our forefathers knew about wood and while YouTube may be entertaining for the armchair woodworker today, it can be misleading when a laboratory style experiment sets out to prove a hypothesis with carefully chosen parameters, when in the real practical world a more complex set of demands exist.

To glue or not to joint, that is the question

This article has been triggered by an almost viral YouTube video claiming that end-grain gluing is stronger than side- or edge-grain gluing – in fact ‘over twice as strong’, which plants the idea in many thousands of minds that glue will conquer all. The traditional way to edge joint large boards – e.g. in a table top – is to use inserts along the glue line – which also locate the boards and keep the top surface flush – but that modern glues can hold those boards together without any reinforcement. I’ve done it myself for years with a 95% success rate. I recall elm being a little tricky because it absorbs moisture easily and moves a lot, so the occasional joints have opened.

Technology & nature

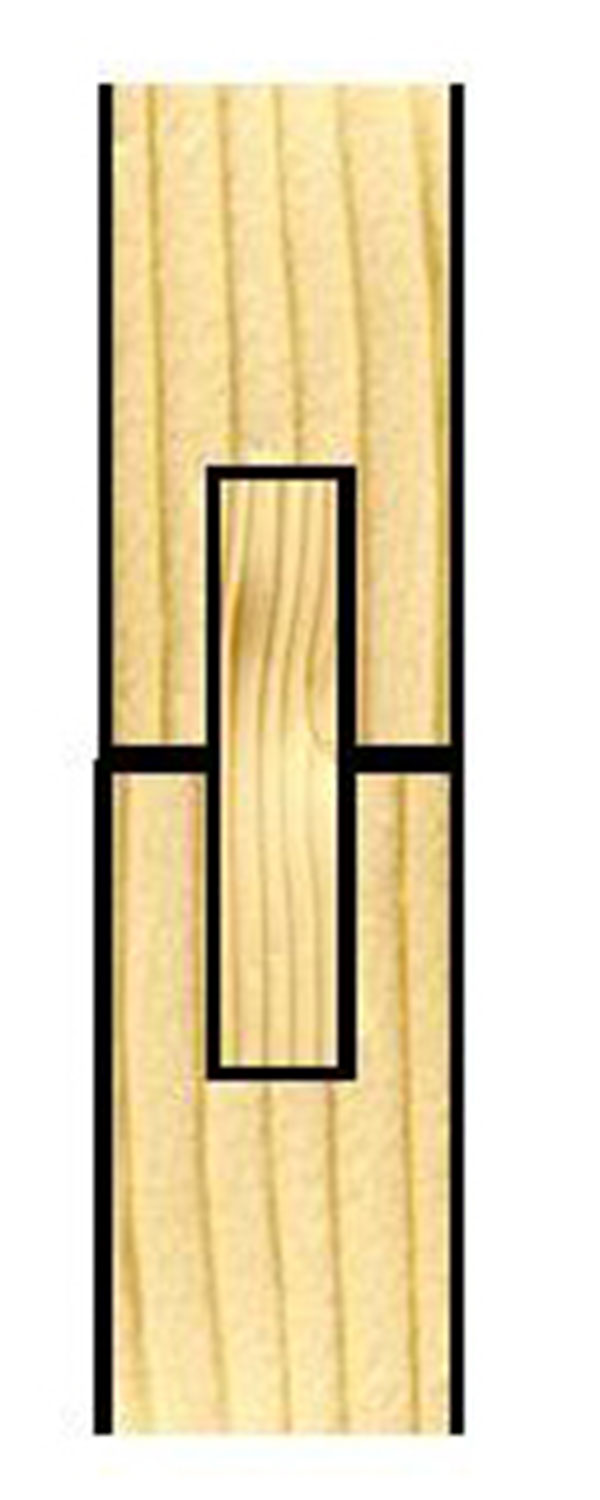

Modern science tailors glues to provide a strong initial tack and fast speed of set, while allowing realignment of working pieces. Cascamite (Extramite) and epoxy resin glues have held boats together in stormy seas for decades. PVA (polyvinyl acetate) glue is the industry standard for interior woodwork as well as low cost, convenient to use and fairly quick setting. Expanded Polyurethane glues thrive on wet wood but are messy to use and clean up afterwards. There are many different glues for different purposes and some are better for end-grain gluing. For example, Titebond ‘No Run No Drip’ aliphatic (PVA) glue, which I tested on a variety of joints in 2013 in a YouTube video and for end-grain gluing, found it to be stronger than Titebond 3. However, the manufacturer advises that although the glue is stronger than the wood, reinforcement to the joint should be added in stress applications. Most furniture making is a stress application. In fact, because the glue is stronger than the wood, we have to look at where wood is weak and that’s in the lignim that binds its fibres together. Imagine a piece of wood as millions of drinking straws held together (photo 1) – they’re strong in length along the grain, but not across the grain.

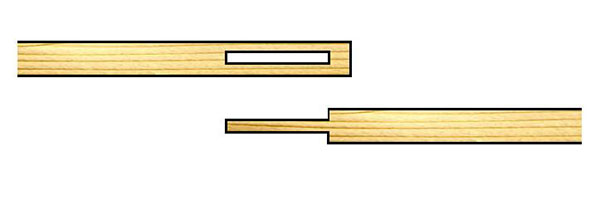

The basis of wood jointing is fibre overlap. End-grain gluing, where the leverage dimension is far greater than the end-grain dimension, is weak and requires reinforcement that offers fibre overlap (photo 2). In my experience, wood is a forgiving material but as with an errant child, the parent has to set the boundaries. Nature usually wins, but there’s no doubt that modern glues are as permanent as the word can mean where the all-important geometry of the pieces being joined is observed.

Time tells

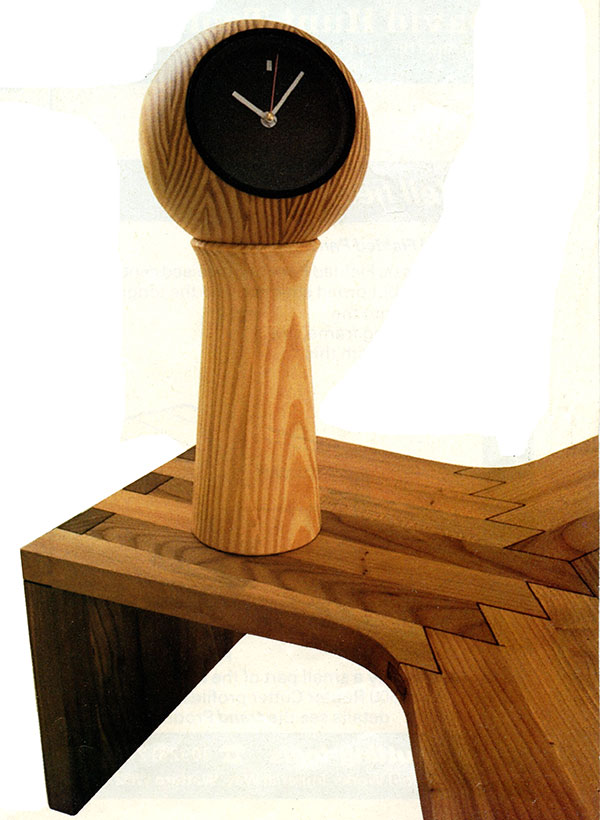

Here I’m sharing over half a century of my own adventures with wood, where I deliberately challenged tradition in the structures and forms I explored and all from the standpoint of having trained rigorously in traditional cabinetmaking skills – see article on Shoreditch College (WW Nov 2020). I still have examples of some early furniture pieces, which have allowed me to observe the effects over the last 50 or so years. Two examples are my ‘Universal Clock’ and ‘Zigzag Table’ (photo 5). I still have the 1972 clock prototype made of pine blocks glued together. There’s no visible movement in the wood; numerous versions of this clock have been commissioned in timbers ranging from pine and oak to Hyedua.

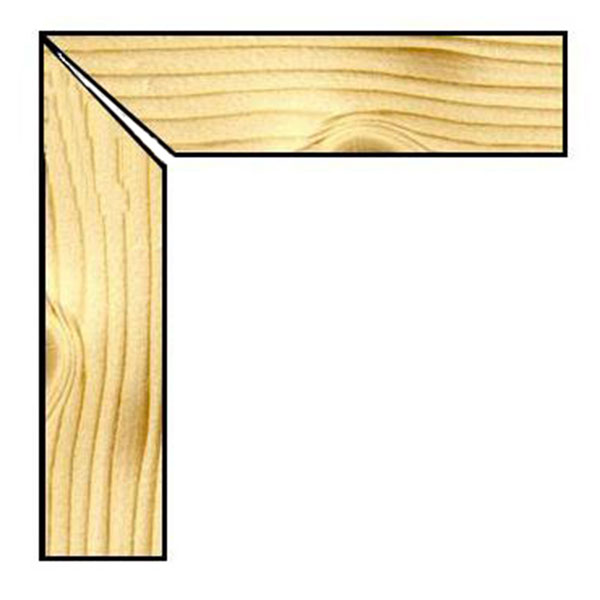

Let’s consider the behaviour of wood and glue subjected to changes in temperature and humidity over a much shorter timescale. A mitre joint is half end-grain half side-grain and when just glue is used, is likely to open up from the inner edge as the wood fibres expand and shrink (photo 6). In a warm art gallery setting, this will happen within a matter of weeks. Most picture framers use some kind of reinforcement spline and in woodworking generally, a glued biscuit or routed insert would hold the joint together.

Challenging the myth of end-grain gluing In some parts of the world it appears a somewhat polarised view has been formed, which says that all end-grain gluing is bad. The English tradition of gluing mortise & tenon joints sees glue applied to end-grain surfaces, whereas in the USA and Canada, glue isn’t applied to the tenon shoulders!

The root understanding of end-grain and gluing is in tradition and the English – British tradition – runs deepest of all. In the old technique of Oystering – parquetry – the end-grain blocks are much thicker than conventional veneers and the glue has a dominant effect on the structural integrity where there’s no leverage force. Using the same end-grain to side-grain configuration in a chair or table leg, the leverage – in different directions – is an essential factor in where a glue-only joint shouldn’t be used.

The strongest joint in the world probably isn’t what you think

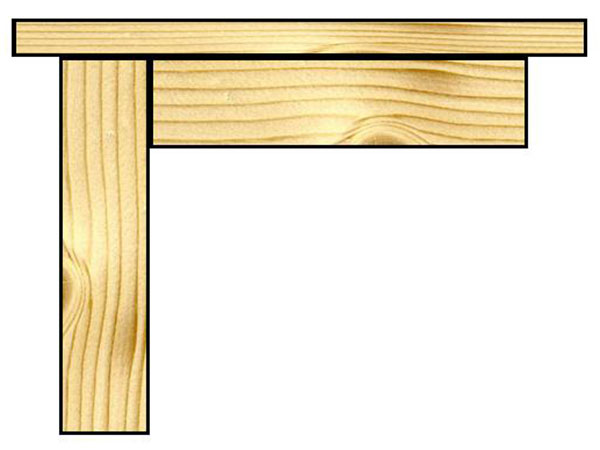

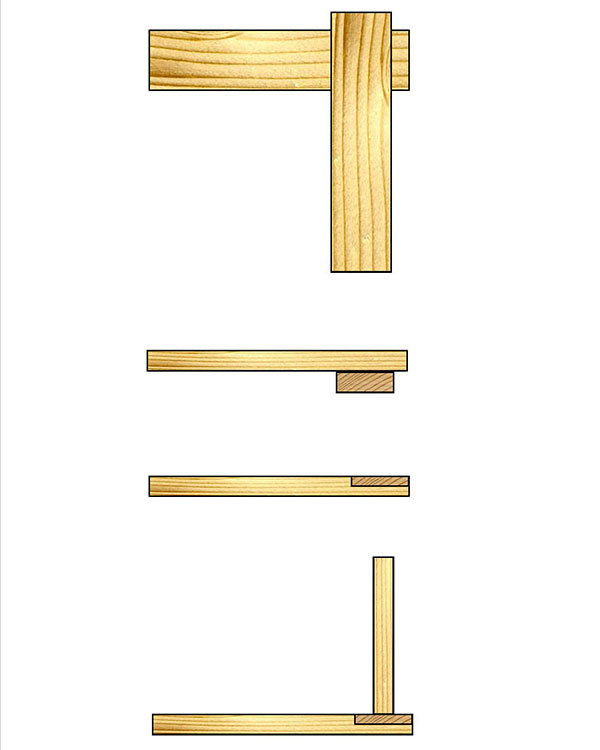

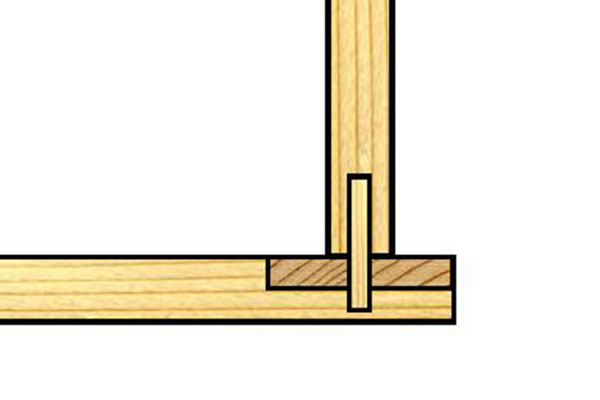

Now, I previously mentioned that the mortise & tenon is unchallenged and most woodworkers would probably immediately think it’s the strongest joint. If you look at the fibre overlap, however, there’s a strength ratio of 2:1 – mortise:tenon (photo 7). For optimum strength, the ratio has to be 1:1. The force of leverage doesn’t ask which is the tenon or the mortise, but finds the weakest part. The only joint that provides equal strength is a halving joint, but it would require screws or glue to hold it together (photos 8 & 9).

Well, or so I thought 48 years ago when I added short screws to the massive glued halving joints in my rocking chairs and other designs (photo 11). But holes severing long fibres actually weaken joints, so I decided to take the risk on glue only and used Cascamite – now called Extramite. The choice of joint and how I machine them allows the sculptural form, which demonstrates the importance of design and designing around available resources – timber and tools. I used a second-hand DeWalt radial arm saw I bought for £50 in 1972, which is still in use today.

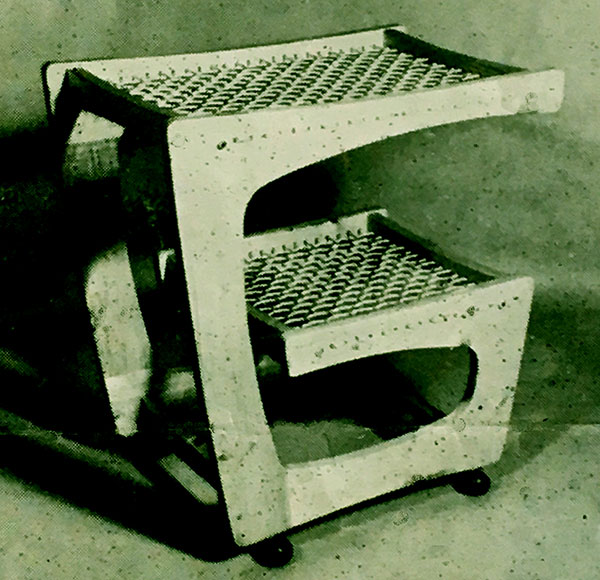

The woven cord featured in many of my chairs and the tea trolley in photo 11 simply involved a Black & decker drill. Necessity is the mother of all invention. Although my furniture was under the spotlight for several decades at major exhibitions, no journalist or critic ever picked up on my unconventional jointing method that depicted my style. The fact that I’m the first person to write about it in 2021 suggests there’s an existing snobbery in furniture making that halving joints are a carpentry joint and therefore not worthy of investigation. There may have been whisperings at exhibitions of course... The word permanent is relative, but they’ve stood the test of time and are fetching good prices in auction houses today.

The all-important relationship between nature and technology points to the geometry of the massive halving joints, which is crucial. If the glued surface area is large and the wood wall thin, the gluing of adjacent grain can stand the test of time provided the wood was dry enough for a proper curing of the glue. In my experience, straight-off-the-saw glue surface aids the bond. Of course, the overall strength of the chair relies on the cross-members.

My Kangaroo Rocker pictured overleaf, of which several versions have been made in elm and ash, uses a massive halving joint for the cantilevered structure. The third member of the side profile is edge-jointed with a cross-grained solid wood insert. The chair has a minimal number of components and early versions – in 1980 – were pack-flat using scan bolts. My rocking chairs haven’t been tested in a laboratory but by prototyping, usage and observing the complex forces that are borne on chairs in particular. Consider also the fact a rocking chair has a moment of force wherever the position of the rock is and the tapering of the rocker isn’t just a question of aesthetics.

Something that’s always in the back of my mind, however, is advice given to me back in 1976 by the late Alan Peters: “Go to a museum where furniture has survived for centuries and see how timber behaves.”

FURTHER INFORMATION

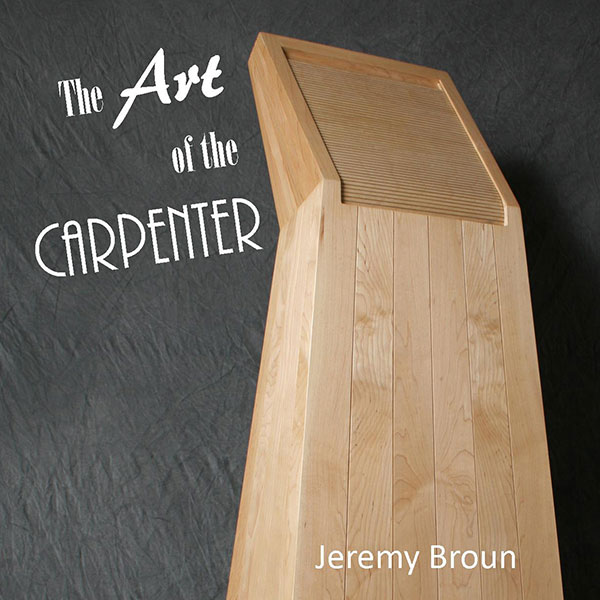

An inspirational book full of woodworking innovation over half a century is available from www.jeremybroun.co.uk.

- Log in or register to post comments