Jobs, joints & journalism

I had the most daunting job in the long history of The Woodworker: I followed Charles H Hayward as editor. His name should be familiar to you. Born in 1898, he lived to be 100, and edited more editions, wrote more books, made more furniture, drew more, knew more and spoke less of his accomplishments than most men far less gifted than he. And let’s just say that in those days, I never addressed him as anything other than Mister – not once as Charles.

I suppose I’d better start by telling you how I came to get the job of assistant editor. This was in 1964: I was 29 and there were plenty of jobs about; no problem with changing place of work. I’d trained for two years in the late 1950s as a woodwork and metalwork teacher at Borough Road teachers’ training college, west London, followed by a supplementary course at Trent Park, in north London, a couple of years later.

As an aside, it’s only recently occurred to me that the design of my furniture pieces made during those years were unconsciously influenced by the Festival of Britain, held some 10 years earlier, and which I’d really enjoyed. All in all, I loved woodwork but hated teaching. So I left. I did a few months’ boatbuilding, a short spell in a furniture factory – got sacked, too slow – repaired some old furniture, declined the offer to take over a one-man business from a picture framer, and made one or two pieces for friends. And then the situation vacant advertisement appeared in the Daily Telegraph. I’d wondered about journalism, knew nothing about it but thought I’d give it a try, mainly because I was so eager to get back to London. The publishers who owned The Woodworker at the time were Evans Brothers – an old family firm in Russell Square, just round the corner from the British Museum.

Two jobs on offer

So, I set off for the interview, which was very casual, but they offered me the position. At the same time, I had another offer from Heal’s in Tottenham Court Road as a furniture salesman. Anyway, the problem was that Evans didn’t think much of my drawing skills, and the offer was conditional on these improving. Well, they did, as I’ll go on to show, but never anywhere near what Charles Haywood was capable of.

And it was only over the following years that I realised how much Mister – remember! – Hayward had accomplished. This story begins in the 1960s, but might go back much further than that. I still have a book of my father’s called The Complete Illustrated Home Book and some of the drawings are so similar to Mr Hayward’s that I could have been influenced by him from childhood.

Now, day-to-day life in the office – what was it like? Quiet, by today’s standards, I’d say. A tall Georgian building, one typewriter, not even a photocopier, tea and biscuits brought into the office every morning, and two phones: one for internal calls and the other for external.

The company’s business was mainly magazines for school use and it was staffed largely, if I remember correctly, by middle-aged to elderly ladies; single, I guess, because their would-have-been husbands had lost their lives during World War I (1914–18). I well remember Mr Hayward telling me that he was wondering how best to explain to our secretary why a plug was masculine and a socket feminine...

I was single myself at that time, but wanted to get married. And just a couple of weeks after arriving, a young woman came into the office from another department. I thought in words that I never lived down – “she’ll do” – and she did. We married a year or so later. That was copying Mr Hayward because he’d done the very same thing himself, some decades earlier, to a girl of the same name.

I have to say that his memory was phenomenal. We received a letter one day asking for information on bending by kerfing – saw cuts made across the width of a timber. Well, in those days, the 12 monthly copies of the magazine were bound into an annual volume. “Ah, yes,” he said, and picking a volume from the shelf next to him, murmured what sounded like: “1930-something, probably October edition, right-hand-page...” And there it was.

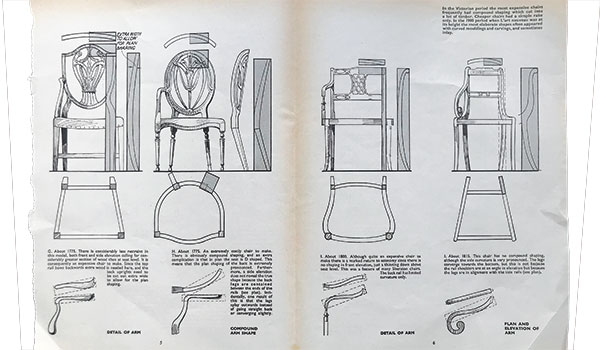

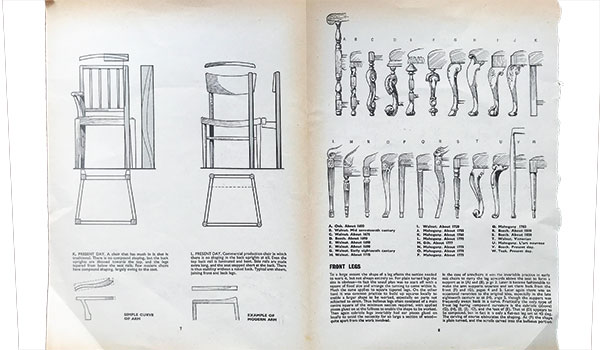

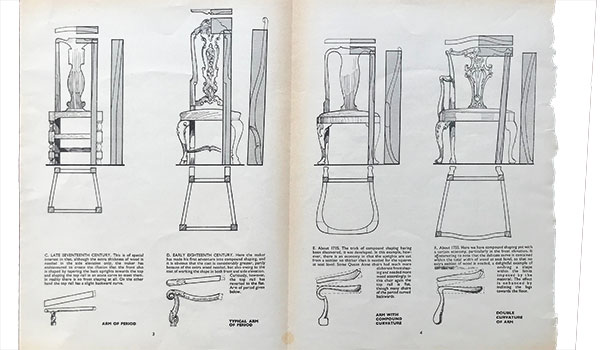

Another memory that sticks in my mind is watching him draw the chairs for the gate-fold insert of the April 1965 edition. Starting from the mid-17th century onwards, almost decade by decade to 1820, just sitting down and doing it. Mapping pen, no reference books, just memory. But . . . well, there had to be a ‘but’ in here somewhere. He’d have stopped there if I’d not stepped in – very hesitantly – to suggest that people might be interested in something more recent. So he added two modern chairs. I think he admired the earlier work so much that he thought later stuff inferior.

The early test piece

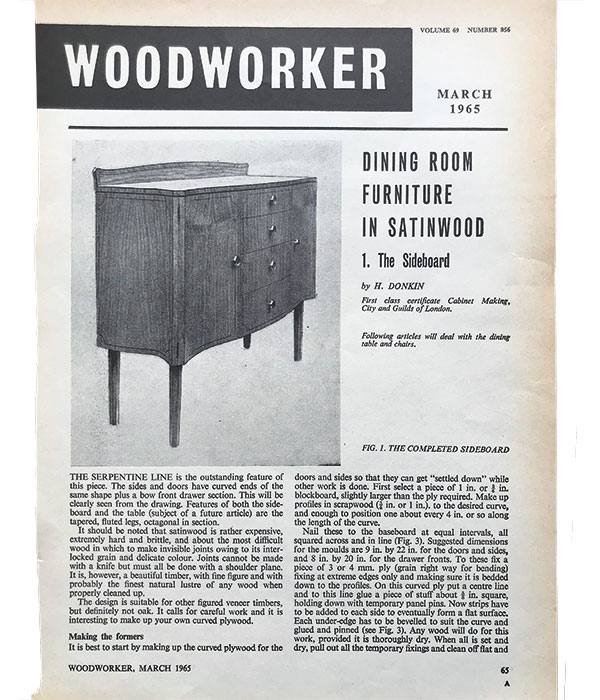

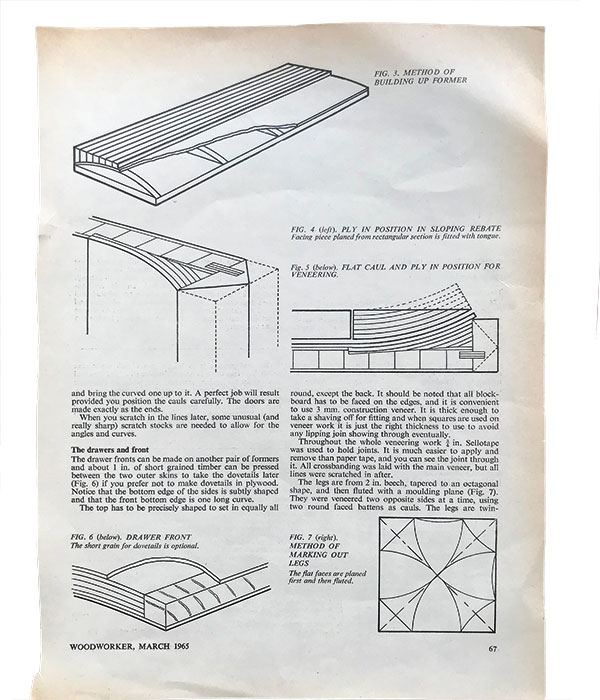

As for my own abilities, I could cut a good secret lapped dovetail; but when it came to drawing, at that point I could just about manage to sketch a mortise & tenon. And the test came early on: a perspective view of a cabinet that was serpentine both in plan and front view. You can see what it looks like opposite; not too bad, I’d say, but clearly not CHH standard.

In all that time, there was only one error, which occurred as a result of a competition we were running to identify plane blades. One answer we gave was wrong and it was noticed by Philip Walker, who later went on, with Roy Arnold, to form the firm of Arnold and Walker – dealers in antique tools and founders of the Tool and Trades History Society (TATHS). I got to know both of them well in later years and they bought from me a low-angle smoothing plane for £120, which had metal sides that were dovetailed – yes, metal and dovetailed – to the sole. Not a bad deal, especially as I’d purchased it for £5 from a man who’d brought it into the office. I had to confess to my, by-then wife, that I’d spent that amount, which at the time and out of my £900 annual salary, seemed a significant sum.

Some fresh ideas

It was at this time that Practical Woodworking made its first appearance. My brother-in-law was working in an advertising agency and saw a dummy copy, distributed in advance of publication in order to get advertising. He told me about it, and I was able to produce a copy at a monthly executives’ meeting. Luckily, we had time to present The Woodworker with a new look before their first issue even hit the shelves.

That was for the January 1966 edition and we began the editorial by saying that the following October of 1966 marked the magazine’s 65th birthday, and we were anticipating the anniversary with a new layout as well as introducing some fresh ideas.

Those meetings managed to be both formal and relaxed: everyone else in suits, white shirts and ties, while the editor was given complete freedom to do as he wished. I’d become editor on Mr Hayward’s retirement, but not without considerable doubts. It was another of my brothers-in-law who persuaded me. We were sitting in the Princess Louise – a fine and ornate Victorian pub in High Holborn. We used to meet there at lunchtime to admire the joinery, and after I’d expressed my fears, he said: “Take it – whatever happens, you can always say later that you were actually the editor.” Good advice.

New developments

One of the benefits of the role was trips out of London to the Forest Products Research Laboratory or the Timber Research and Development Association, to see new developments. One that particularly stands out in my mind is where they’d steam and compress a length of timber along its length, and it would remain flexible even when cold. As regards previous editors, before Mr Hayward was JCS Brough, author of Timbers for Woodwork, and I think he’d been in the job for many years; I was possibly only the fourth editor since the magazine’s inception.

Sadly, I was forced to resign towards the end of 1967, due to family, commuting and house prices, but it was the best job I’d ever had. After me came Vic Taylor, a previous assistant editor, who was still doing some freelance work for us. After him was an editor who’d worked on a forestry magazine – Zachary Taylor, I think – whom I never met. His is a name I remember, however, and I think he later had something to do with Ely Cathedral. My assistant editor, Jan King – cover star of the June 1968 issue shown on page 36 – with whom I remained friends, stayed on for a while before sadly passing away at the age of 39.

So what was the overall situation with woodworking at that time? Leaving aside working conditions and health and safety – there were some horrific stories – I suppose that until 1914, the old craft traditions still very much existed. I guess they were diminishing during the inter-war years, although I can remember seeing in the office a timber merchant’s catalogue from 1939 offering quartersawn English oak, planed all round from 1/4in thick upwards, and in any number of widths.

Hard to find

By the time I was working on the magazine, good hand tools – anything other than the basics – were hard to find, and even the power drill was in its infancy. People were still influenced by Barnsley and Gimson, but the swinging ’60s weren’t much in evidence.

Around 2000, I met many of the young generation of furniture makers setting up in Shoreditch, east London, which, as many of you know, is the traditional home of the trade. What came as a surprise to me at that time was the number of young women taking up furniture making. One of them, I recall, had been working in Paris for many years. In another workshop were a group of five women, who I think were attracted by the premises’ low rent, all of which made me think that the future was in safe hands.

One final question for today’s editor: is the magazine called Woodworker or The Woodworker? To this day, I’m still not sure!

- Log in or register to post comments