Keeping Up Appearances

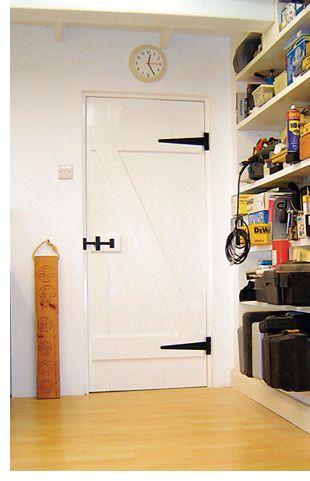

My workshop began life as the milking parlour in what was once the cow shed of a small 16/17th century farm. As you might expect, centuries of wear and tear have meant that the farm now features a rather eclectic mix of doors: though they’re generally of plank construction and in the style of the vernacular ledge door, they range from the original oak three-ledge doors, through to Victorian softwood ledge-and-brace designs, to post-war softwood ledge doors, with either early hook and band or later T-hinges variously mounted on the front, on the back, on the ledges, and on the planks.

When planning to build a new door for the workshop, then, I had no shortage of models to help me design something that would be in keeping with the rest of the place. Apart from the original oak doors – which have long since settled into their correspondingly crooked frames – those doors that have fared best are the Victorian ledge-and-brace examples, which seem to have been made from the same basic timber as the square-edged 1 x 6in (25 x 152mm) floorboards as the other ‘improvements’ dating from the same period. The Victorian doors have either two or three ledges, held together with clenched cut clasp nails, with either Norfolk latches (which evolved from the Suffolk latch by adding a backplate to the handle) or rim sash locks depending on whether they’re in the house or in the farm buildings. To remain in keeping with the rest of the property, I decided that a basic door would suit the cow shed, and settled on the Victorian model based on 1in floor boards, with a twin ledge and brace, hung on hinges mounted inside on the braces, and secured with a Norfolk latch.

Victorian measures...

Victorian measures...

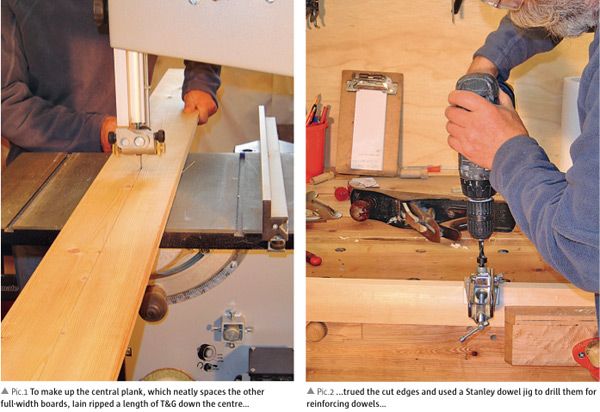

The first thing that became apparent when I started work was that Victorian 6 x 1in flooring was precisely that – six by one. While today’s proprietary timber may start out being sawn to 6 x 1in, however, machining produces a planed-all-round (PAR) board of 53⁄4 x 3⁄4in – or 145 x 20mm in our world of mixed-measure timber. What’s more, while the Victorian tongue-and-groove (T&G) boards have a full 6in of timber between the tongue and the groove, modern machining further reduces the PAR board to leave you just 135mm (51⁄3in) of width between the tongue and groove.

When I looked still closer at the original doors, I realised that, even down on the farm, the Victorians’ attention to detail extended to building the doors around a central ‘bespoke’ plank, whose width was tailored to allow the rest of the door to be made up to the required width using full 6in-wide planks, which lends the door a nice symmetry.

You can see, then, that the difference between a ‘reproduction’ door and one that’s ‘in keeping’ can be partly measured by the extra work and expense involved in replicating the dimensions of the timber originally prepared by Victorian apprentice labour, rather than simply using off-the-shelf boards. My workshop door was definitely going to be one made to be ‘in keeping’!

...and modern methods

...and modern methods

That said, although I accepted the proprietary T&G boards and their reduced width to make up the majority of the door’s face, I couldn’t bring myself to use them as edge boards: trimming off the tongue and the groove – which would have been the obvious way to create clean edges – would have made them so narrow as to spoil the look of the door. Instead, I used two lengths of PAR timber, one of whose inside edges was finished with a tongue, the other with a groove so that they not only mated with their neighbours on one side and show clean outside edges on the other, but present a face that’s the same width as the T&G boards.

The rest of Iain's article can be found in Good Woodworking issue 218

- Log in or register to post comments