A sign of the times

Illustrated signs

In medieval times, alehouses were ordinary homes where the occupant both brewed and sold ale and beer. Taverns sold wine, which was more expensive, and were patronised by a richer clientele. In time, alehouses became public houses, and taverns, coffee houses; however, alehouses, inns and taverns all displayed wooden signs.

In establishments where ale and beer were drunk, landlords placed a wooden hop pole or ale stake over their doors. Some were unduly long, however, and could constitute an obstacle. This gave rise to a short projection, on which a sign could then be hung. In 1393, King Richard II made ale signs compulsory, and, to attract business – and as few people then could read – proprietors had these illustrated. Richard’s own emblem was the white hart, with other regal examples being the white lion (Edward IV) and white boar (Richard III).

Royal & religious origins

Hardly surprisingly, undoubtedly the most common British pub sign, ‘The Red Lion’, was also of royal origin. When James VI of Scotland assumed the English throne in 1603 as James I, he decreed that the red lion of his home country be displayed on all important buildings in England, including drinking establishments.

Up to the 16th century, with an eye to the then considerable custom from people travelling on pilgrimages, innkeepers choosing signs often favoured religious images. One such example was ‘The Mitre’, which reflected the hat of a bishop or senior abbott; ‘The Ship’ was a reference to Noah’s Ark; while ‘The Crossed Keys’ called to mind those by which St Peter could unlock the gates of Heaven.

In the 18th century, increased popular transport was reflected in pub signs, such as ‘The Coach and Horses’, and ‘The Station Arms’. In Stony Stratford – near modern Milton Keynes – coach passengers bound for Birmingham, and others for London, used to drink and talk together while their horses were changed. They did so at neighbouring pubs called ‘The Cock’ and ‘The Bull’, thus giving rise to the phrase ‘a cock and bull story’.

The sign making process

Until largely supplanted by digitally-screened images during the 1990s, hand-painted pub signs in England enjoyed a strong tradition. The well-known brewer, ‘Whitbread’, had its own art department, whose studios occupied a former malthouse at Cheltenham. In time, it was renamed ‘Brewery Artists’ and relocated to Gloucester, but also closed down in the early 1990s. Besides ‘Whitbread’, it undertook commissions for brewers such as ‘Ansells’, ‘Brains’, and ‘Eldridge Pope’.

In making a pub sign, the first stage is to obtain an appropriate base for the design.

This would normally be made of exterior or marine ply, by a professional joiner, and with a softwood or hardwood frame. The bare board is then sanded down, and at least two coats of aluminium primer applied, followed by two of undercoat, and two of gloss. Next, an outline of the motif is made on the surface in chalk or pencil. The design itself is then painted on, using a special oil-based enamel employed by signwriters in general. One of the tools used – a ‘mahlstick’ – is centuries-old and comprises of a stick with a pad for steadying the artist’s painting hand.

Modern paints are more weather-resistant than their predecessors, and most signs last between 5-15 years. Wear is quickest in coastal settings, where salt in the air eats at the paint surface, combined with seagull droppings, which are very acidic. Old signs often attract ready buyers, as many people admire the patina that develops on them over time.

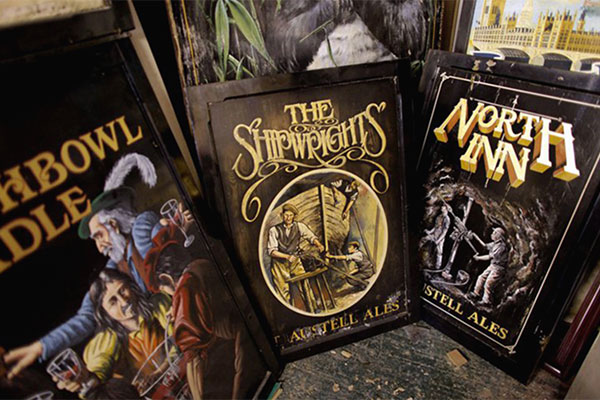

Andrew Grundon – sign painter

Andrew Grundon is an artist prompted into sign painting to ensure regular work, which commissions in wildlife, landscape and portrait painting alone had denied him. After gaining useful tips – such as gilding with gold leaf and font styles – from the then soon-to-retire resident sign painter at St Austell Brewery, he went on to form his own company, ‘Signature Signs’, which is based on Bodmin Moor, in Cornwall. A bonus lay in the brewery becoming a client.

Some of Andrew’s designs are very traditional, having been established centuries ago. Though not short of imagination, he doesn’t hesitate to use literary sources for ideas, for example. A fair proportion of pub signs celebrate an occupation, and here careful checks are required to ensure historic accuracy, especially when it comes to mining and blacksmithing.

Roman ingenuity

Even prior to Roman invasion, wine was being imported to Britain, and large storage jars – called amphorae – excavated at Roman sites suggest the sources were

Italy and Spain. Civil war in the latter disrupted trade around AD 200, but the empire’s geographical reach meant alternatives, notably France and Germany, could be relied on. An example of Roman ingenuity was the screw press, employed to squeeze olives for oil and grapes for wine. Making one in wood is very challenging:

to do so, a thread must be cut on the vertical screw as well as within the hole into which it fits.

Literary signs

A few pub signs stand out in literature: The Canterbury Tales, by Chaucer, opens with the would-be pilgrims to that city assembling in London, at ‘The Tabard’ inn, in Southwark. Modern dictionaries describe this garment as a sleeveless jerkin, but in Chaucer’s day, it was a herald’s official coat, emblazoned with the arms of the sovereign, so this sign would therefore have been bright and easily spotted.

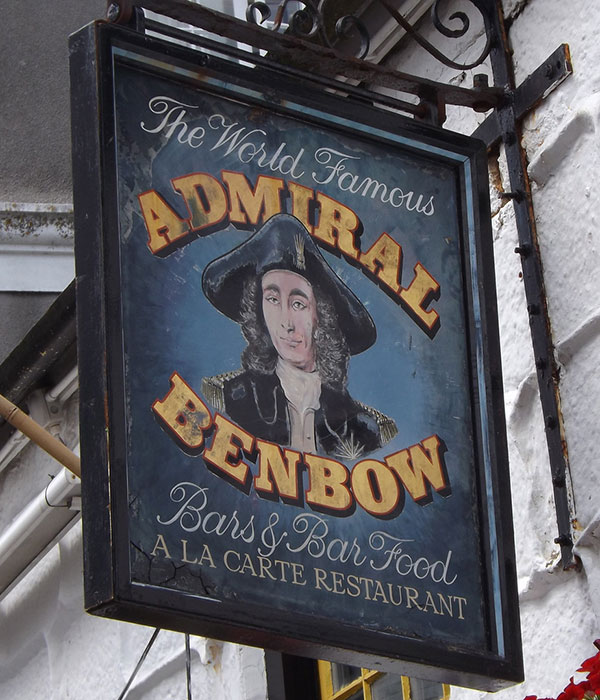

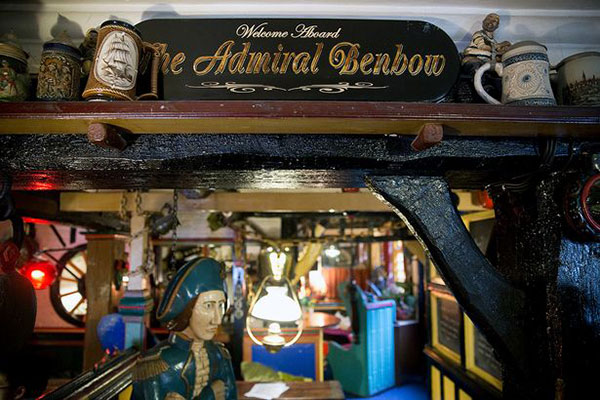

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island is another classic to feature inns. Much of the story takes place on or near the sea, and from the beginning, narrator Jim Hawkins mentions two, which prove to be significant locations – ‘The Admiral Benbow’, and ‘The Spy-Glass’ – each name reflecting the maritime setting. Early in Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s famous novel on whaling, the narrator, Ishmael, seeking a place to stay, comes across a tavern: ‘... and, looking up, saw a swinging sign over the door with a white painting upon it, faintly representing a tall straight jet of misty spray, and these words underneath – ‘The Spouter-Inn.’’

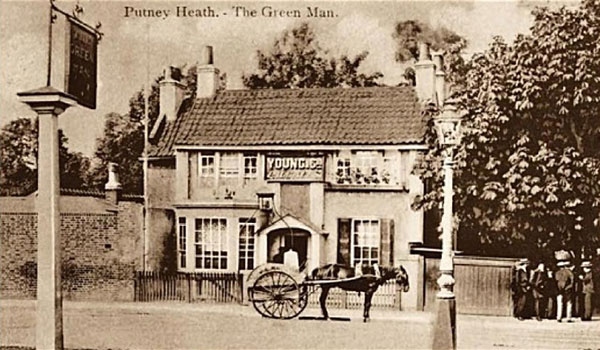

The green man

Though fairly common in certain parts of the country, some pub signs invite explanation. One such is ‘The Green Man’, usually represented as a face composed of – or surrounded by – leaves. Though invoking an ancient tradition, the term itself was only coined in the 1930s, before which they were called ‘foliate heads’, and appeared as carved features on old churches.

The Green Man is often portrayed with acorns and hawthorn leaves – symbols of fertility in the medieval period – and the renewing of life in Spring. This constitutes a notable instance of how Pagan symbols of nature and tree worship were incorporated early on within Christianity. As a pub sign, the image is probably most commonly found in Devon and Somerset, but also appears elsewhere. ‘The Green Man’, in the Putney area of London, dating from 1700, was notably a highwayman’s haunt, and very old village establishments bearing the same name are also situated at Kings Stag, Dorset, and Long Itchington, in Warwickshire. Pub signs bear their names for sound – if sometimes obscure – reasons, and in total offer a fascinating reflection of English history and social change.

- Log in or register to post comments