The Alan Peters Online Furniture Award 2024 – make your entry count

With the entry deadline for the Alan Peters Online Furniture Award 2024 only months away – 31 July – some woodworkers might be wondering: ‘Am I up for it? What can I make especially for this award?’

In this article, I’m going to share how I asked these very same questions when Alan Peters gave me a break in my career. I’ll also discuss the importance of exhibitions and awards, setting briefs and deadlines for them, and also speculate on what changes Alan might make to his use of tools if he were alive today. He sadly passed away in 2009.

Talent spotting

In 1976, Alan was talent spotting work at college final shows when my furniture designs, at the High Wycombe College of Art – later to become Bucks College – where I’d completed a rather disastrous post-graduate year, caught his eye. At that time, it was geared towards industrial designers and I was probably the first designer-maker the college had seen. With no previous design training, I’d been running a small workshop in Bath for three years previously, selling my unusual modern furniture designs.

A year or so later, Alan contacted me with an invitation to exhibit my work at a major British show called ‘Flavour of the Seventies’ with himself, John Makepeace and a couple of other top names. I was the complete unknown.

In Alan’s letter, he said he was ‘staking his reputation’ on me. It was very much a name game then – as it is today, of course, but to a lesser degree due to the democracy of the internet in that talent doesn’t rely on being curated to be seen. However, it’s a mark of Alan’s character to give innovative unknowns a break and those who hadn’t trained at the Royal College of Art.

I recently watched a riveting documentary on Michael Schumacher, and how he was a fresh unknown youngster and given a chance alongside the big names in Formula One racing when he was taken on by Benetton. Not that I’d draw any comparison between myself and Michael Schumacher other than I too have always been fearless – for me it’s been in pushing the boundaries of furniture design, with tools such as the router, which I discovered many woodworkers are afraid of!

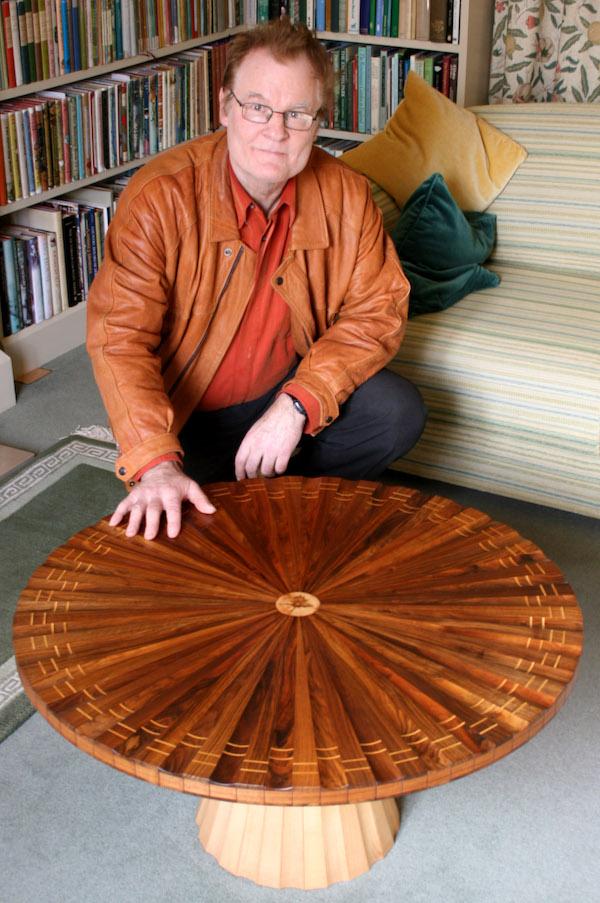

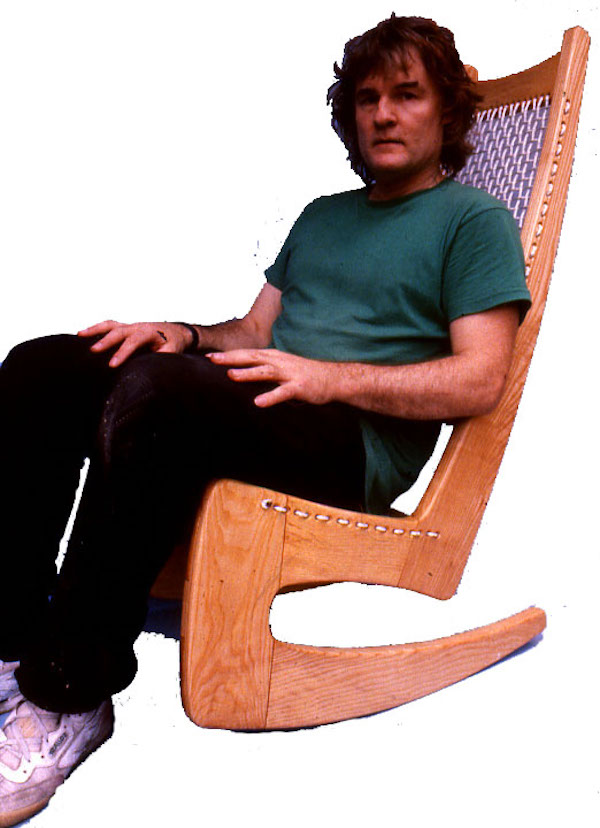

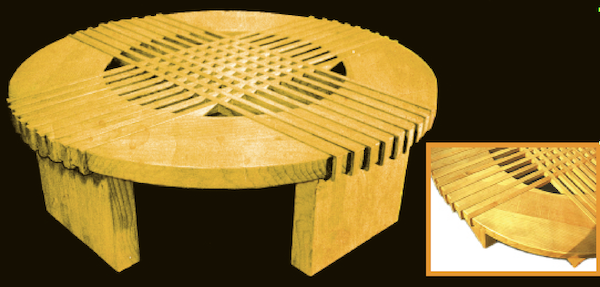

For this major group exhibition, I made one of my trademark high-backed rocking chairs, which years later was requested for a Royal Family viewing. I created one of my most innovative pieces to date – the ‘Zigzag’ table in elm and the ‘Millstone’ table in cedar of Lebanon. I’d been offered a cedar of Lebanon tree from the Robertson’s Jam family estate near Bath and only had room for a small portion to be converted into 50mm boards.

I recall running out of wood for this table at 3am and had to cut the remaining timbers into stout veneers, so the legs had a core material of chipboard. This was 3am the same morning I had to deliver my pieces to Southampton Civic Centre. I think I had about three months to create new pieces alongside paying my workshop rent by taking on bread and butter work making fitted wardrobes and kitchens.

Deadlines & factory experience

Any professional joiner or furniture maker knows the importance of deadlines. Customers don’t expect the off-the shelf service you get from a store and are happy to wait 2-3 months for a piece, which is considered normal. But for this and other exhibitions, I usually had about three months to create a number of special pieces. The designing is what can take the time and the thing about opportunity is that you grab it.

Deadlines aren’t just completion dates allowing for interruptions, etc. but targets to set each day. In 1985, when I taught full-time at Rycotewood College for a year, I was responsible for the first year group. They nicknamed me the ‘Deadline King’ as I set half-day targets. I was unpopular at the time as other tutors weren’t so strict, but they thanked me when I visited the college show a year later. I put my own experience down to a valuable period spent working in a local furniture factory, where we were on bonus piece rate.

Stimulus for new ideas

An exhibition or award is an exciting opportunity and a great stimulus to create something new, and for several decades, I can say that most of my exhibition pieces sold as a result of these. Of course there’s always a danger that whacky, impractical designs are on public view when competing with fellow exhibitors, but the public in general wants practical, useable furniture that looks good and won’t go out of date. On several occasions when delivering a piece, I noticed that the client had also bought an Alan Peters piece. This is because our work was rooted in tradition, but as Alan once said to me: “We sometimes get stuck in tradition, but it should move on.”

Playing with ideas

So, tradition can be a stimulus for new ideas. In my case, I thought traditional mass-produced furniture was backward looking and unimaginative, and just badly designed. I think the Italian company, Ercol, was the only mass producer to stand out as making furniture that was both practical and desirable. Even today – take outdoor café tables, for example – they often have four legs, so therefore rock!

A three-legged table is automatically stable. So my ‘Zigzag’ table has three legs, and when I sketched the narrow boards joining up in the centre, they depicted the zigzag joint by accident. I then featured a 1.6mm wide routed groove to highlight the joint as it first looked like wood flooring.

Playing around with the idea as you go along is one approach to designing, especially in the case of a chair. In addition, mock-ups and chipboard prototypes can all help the design to evolve.

The design brief

It might be a useful exercise to set out some parameters, only some of which you might stick to. So let’s set out an imaginary brief for an entry to the Alan Peters Furniture Award, and assume you have a small workspace with limited equipment:

1. The piece is small – maybe a jewellery casket or coffee table;

2. It uses native, solid wood but perhaps also plywood;

3. It expresses a concept – such as ‘dovetail’ in terms of both mechanics and aesthetic;

4. It can be made quite easily;

5. It says something innovative, however modest;

6. It expresses technique and material;

7. It’s very well made;

8. It could be a prototype design for a small-scale manufacturer;

9. It’s intended for domestic use.

So, this is a suggested brief and you can see that there’s a wide berth here for both amateur and professional woodworkers. The piece might be for outdoor use and in the past, applicants have included wooden lamps. The importance of this brief is that the tighter you make it, the more creative your solutions can be.

At Rycotewood College, students were set challenging briefs using limited materials. With this award, you’re given the opportunity to choose your own brief. Before applying for the award, it’s a good idea to read my 65-page ebook about Alan Peters’ life and work – offered free of charge to those interested in doing so – to see how simplicity and visual understatement were hallmarks of his furniture.

Judging the award

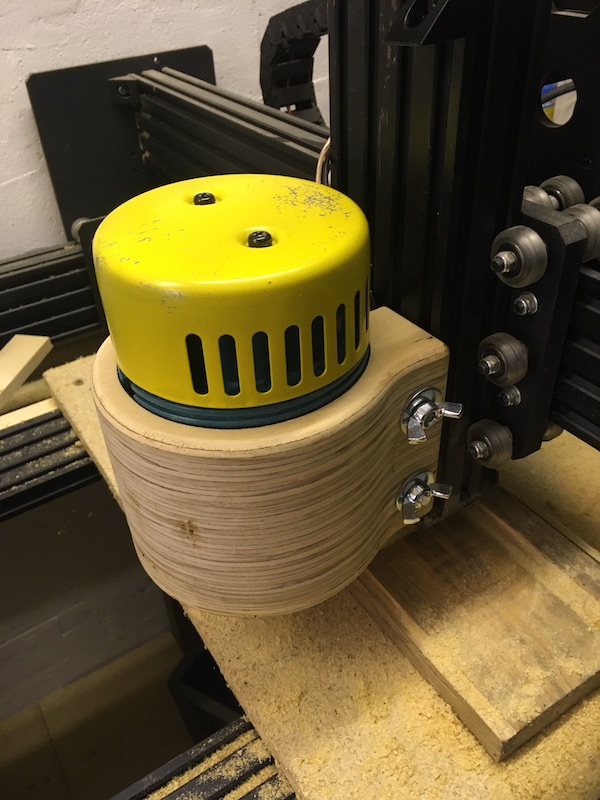

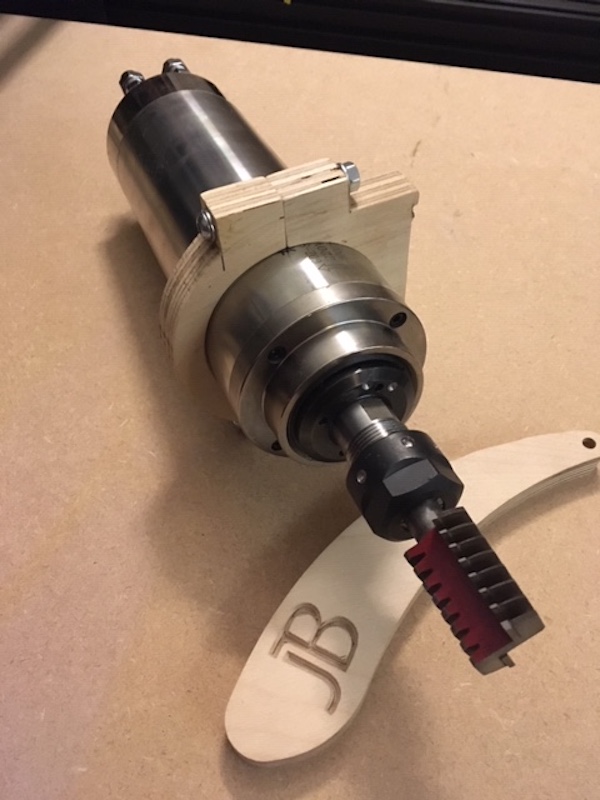

The biennial award is judged by myself and Andrew Lawton, who also knew Alan well – in fact, he was asked to complete Alan’s last commission. So as judges, we often ask ‘what would Alan think about this or that?’ Invariably the discussion concerns tools and machines. It was my initiative to allow a small CNC input and I had to argue my case that to ignore CNC would narrow this award to a purist ethos and exclude a technology that’s increasingly used today. After all, machines were used when Alan Peters served his apprenticeship to Edward Barnsley and Andrew tells me that Alan himself changed his view on using a router.

The same ethos applies to CNC – providing it’s intelligently used, it enhances the craft. Two makers in particular come to mind in embracing this technology – John Makepeace and Barnaby Scott of Waywood Furniture. But of course the Alan Peters Furniture Award emphasises hand skill for the very good reason that we believe a thorough understanding of wood comes from using hand tools, which should first be mastered. Of course, in a commercial workshop, it can be quicker to pick up a hand saw than to jig up a machine.

If he were alive today, I’m by no means convinced that Alan wouldn’t have embraced CNC technology, because he enjoyed usingtools and encouraged innovation. I say this because I’m currently building a CNC machine as ‘a tool’ and controlling it with an Xbox-type controller for some simple, precise and time-saving operations before learning the software. But that’s for another article...

If you knew Alan Peters, please do email the Editor – [email protected] – sharing your views.

FURTHER INFORMATION

The Alan Peters Online Furniture Award 2024, including link to Alan Peters The Makers’ Maker enhanced ebook: www.jeremybroun.co.uk/alanpetersaward

YouTube video outlining 2024 Award guidelines

- Log in or register to post comments