Root & branches

Squeezing past the carcases of half finished furniture, and threading between the makers who’re wielding hand tools, working at a huge tablesaw and around a state-of-the-art vacuum press, we finally reach the narrow design office that is the nucleus of Matthew Burt’s industrious workshop. He lifts his eyes briefly from his drawing board and shakes hands: “Hang on a minute. I just have to finish this layout; I’ve got a big presentation tomorrow.”

This frantic little hub is perhaps all the more unusual for being in Sherrington, a quiet Wiltshire hamlet where a bicycle constitutes heavy traffic. As such, it seems an unlikely home for Matthew who — his 58 years and socks-and-sandles combo’ notwithstanding — is dynamic, excitable, forward-thinking, and busy as heck!

“I’ve just come back from France, by the Italian border,” he says, sitting back. “We’re re-fitting a chalet floor by floor. We’ve done six and a half of the rooms, and they’re full of statement, ****-off pieces.” He’s designing for 10 clients at the moment, and the one he’s hoping to win over tomorrow sounds like the most exciting: “Eight major pieces, refurbishing a beautiful Georgian house with four-metre high ceilings. The client is imaginative, and very appreciative of modern work.” To keep up with the work, there are six full-time makers on site, but there’s so little slack that if one of them is off sick or on holiday, the displaced work has the production line groaning.

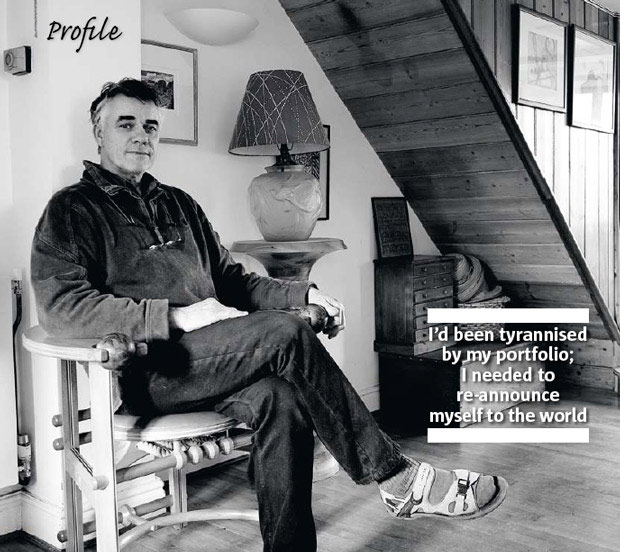

This chair was made in recognition of the rising importance of marketeers in the artworld. See the rollable balls fixed to the armrests? “I thought a marketeer would appreciate a pair to play with,” Matthew smiles. Now standing in the hallway of his house, this piece provides Matthew with a constant reminder of what he calls his ‘decadent period’ which, he says, “tended towards vulgarity.”

Despite this, you soon get the feeling that Matthew thrives in his workshop’s hot house environment. Unlike David Oldfield (GW198:26), who accepts that his solitary working practises mean that some of his schemes will never see the light of day, Matthew is anxious not to leave out even one of his ideas. In the past, he explains, this ambition has meant he stretched and even over-reached himself. It was frustration, that led him to create his team of helpers: “I wasn’t able to get my ideas out quickly enough; they were tumbling out of me.” Now, his diligent makers manage the lion’s share of hands-on work, allowing Matthew to focus on translating that out-pouring of designs to the drawing board.

Given this desire to be up and creating in timber, it’s surprising to learn that Matthew didn’t pick up a woodworking tool until he was 24.

Born and bred on a farm in Wiltshire, Matthew describes his childhood as, “isolated but imaginative. My tools in those days,” he adds, “were my catapult, knives, and fags!” He went on to study botany and zoology at Rycotewood College, but principally because a formal education was what his parents wanted for him: “It was the correct, lower middle-class way of bettering oneself.”

The trajectory of Matthew’s life changed dramatically soon after he finished his studies, however, when his father died. “I was very angry because he was young and he hadn’t necessarily done the things he’d wanted to. It made me focus on the fact that, whatever I did, I had to follow my soul.”

Matthew had always liked drawing and tinkering, but taking up furnituremaking was hardly the obvious step to take. “There was this guy I knew,” he recalls, by way of explanation, “who had to graft hard to [pay his way] through university —totally different to me. Anyway, he made this piece of furniture for his girlfriend; it was messy and far from perfect, but he made it. He produced this object.” After years of communicating in the language of academia, Matthew had come across someone who could express himself through a different, practical language. “I wanted to speak that language!”

And it was simple as that, was it? One moment of revelation, and his future path was decided? “Well, it was a different era then,” Matthew admits. “I asked [Rycotewood] to let me do a two-year course in one year, and they said ‘yes’; I gained just enough skill to get an apprenticeship.” This took him to the Cotswolds, where he was able to indulge his love of nature and the environment.

After three years, he moved back to Wiltshire. “My wife and I worked as gardeners for a year,” he muses, “and we saved up just enough money to get our own house. All the hippies were living on next to nothing, so having no money didn’t matter; it was cool to improvise.” He refurbished the 18 x 18ft shed in the garden and, in ’78, opened his own workshop. “At first, I only had hand tools,” he smiles. “I used a local joiner to plane and thickness while I slowly acquired machines.”

This belief has led to the building of a showroom in the busy town of Hindon, which he stocked with newer, speculative work. He calls this the lifeblood of the business because the showroom gives Matthew a public profile that the inherently private nature of commissioned work never could. Moreover, it allowed him to, “re-announce myself to the world,” — something he felt he needed to do, “because I had been tyrannised by my own portfolio.” With the showroom, Matthew constructed a new portfolio, one that enabled him to steer clients toward the kinds of pieces he wanted to make, rather than the ones he had already made. If he hadn’t squared up in this way to realities of competing in the age of mass-manufacturing, it’s likely that he would never have achieved the financial freedom to express what he calls his post-Enlightenment take on furnituremaking.

Today, Matthew Burt is a recognised and well-respected brand, known for creating furniture that is neither gratuitously experimental or stagnantly nostalgic. Instead, it’s relevant to now. “I’ve always been attracted to simple furniture, designed by the everyman,” he elaborates. “For a zoologist, the best designer is natural selection. Look at a feather. Evolution has suited it perfectly to its purpose, and it appeals to me that, over generations, thousands of ordinary makers can improve a design until it’s difficult to improve upon.” The Windsor chair, he suggests, represents a pinnacle of evolution in much the same way as the feather.

This, then, is why Matthew has assembled his very own crew of ‘everymen’, collaborating with them to create purpose-built furniture for the present and beyond. And it’s with good reason that he resents the general lack of regard that’s accorded to today’s makers, whom he sees as the unsung heroes of the arts.

“The industrial revolution was started by philosophical artisans,” he contends, “who saw all cultural pursuits as important to the fabric of the nation. But the cultural significance of the maker” — with all his skills and knowledge — “is no longer valued in the sound-bite, quick-fix mentality of the modern era.”

quick-fix mentality of the modern era.” That said, Matthew has seen signs of improvement over the last 10 years. “Whatever you think of them, at least Labour said, ‘Let’s be proud of ourselves in our time’. I don’t think it was intentional, but they opened the door, they gave permission [for] a cultural shift in architecture, furniture, design.” In fact, Matthew might go so far as to say that the ebullient self-confidence that these disciplines now enjoy has almost made this a new Georgian age. Not that he’s looking back to past glories, mind: he’s out in the world, from Saudi Arabia to the States, helping to keep his vision for timber alive and relevant in a difficult and uncertain future.

It’s a task that isn’t without its doubts and uncertainties. “There’s intense anxiety about how we keep the show going,” he admits, “and regular three o’clock boardroom meetings with my wife.” Counterbalancing those doubts, though, is the ‘root and branch’ approach — what Matthew calls his ‘post-industrial means of making’. He hasn’t limited his vision for timber by restricting his ideas to himself and his own capacity to make. Instead, the extended self that is the designer-and-makers team combines a creative mind with a commercially viable body to produce a brand that’s not only greater than the sum of its parts, but which has both artistic and financial integrity.

- Log in or register to post comments